For the second time on this show, proof that not every match has to be the biggest and most sensational version of itself to be great.

Dick Vrij and Akira Maeda, very likely the two best wrestlers on these initial RINGS shows (give or take a Willie Peeters), have something more in them than a simpler match and, whether or not this is a good or bad thing, also likely longer than eight minutes. It is a relatively simple match, all about kicks and knees, and — although the shorter runtime helps make this a non-issue — there is not a whole lot of variance in those moments either.

This is one of those times though where these things don’t matter, because other parts of the thing make up the difference.

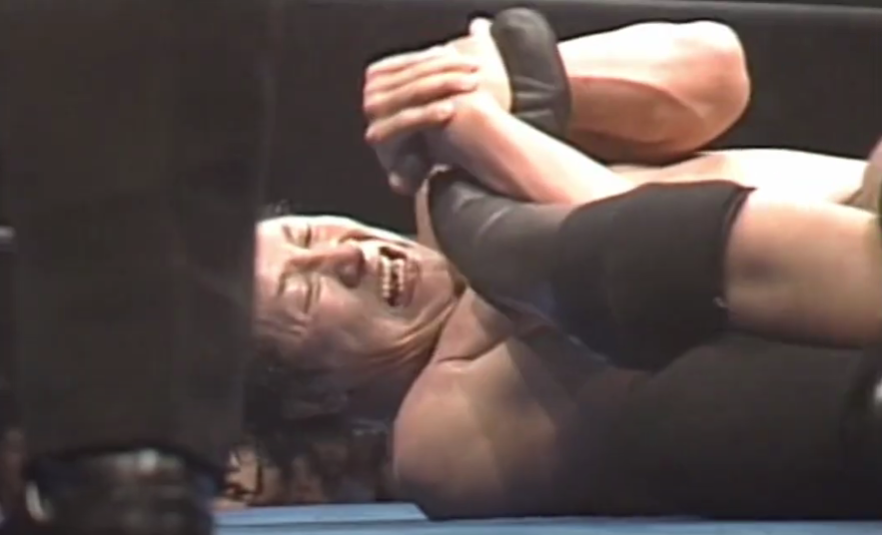

Maeda comes in with a heavily bandaged left knee, and although Vrij rarely goes to it — he does manage to catch it once or twice in moments that feel like pure misfortune for the boss more so than a plan, or even just good fortune for Vrij — it inhibits Maeda in such a way that it makes victory essentially impossible. Some of the best selling of his career, particularly in this sense, comes in this match, not in a flashy orr obvious way, but moving gingerly and then seeming to try and limit movement in a way that Maeda rarely does. Narratively speaking, it also creates a real crushing feedback loop as every attempt to find a quick way out through kicking and swinging for the fences just makes it worse. Once he can’t do it the first time, it’s a lost cause, and after that, Vrij never quite lets himself get trapped on the mat long enough to spoil a gift like this.

Vrij kicks the leg out for the penultimate down in the one time he seems to aim there on purpose, and sensing it, he attacks Maeda more directly than ever. No feinting or stepping back after every second or third shot, but cornering Maeda and hurling shots out faster than ever, until he goes down and our hero Dick Vrij gets a TKO upset. It’s a phenomenal finish, the knee both preventing Maeda from moving faster as well as arguably buckling under him when it might not have otherwise as well as costing him enough downs to get to get to that point to begin with, and the absolute perfect one for the match they had.

Combine this, the might of a simple and perfectly executed approach, with the qualities present in this match that were always going to be present between them. All the mean little slaps and nasty kicks, cool takedowns and blocks, a quietly stellar sense of escalation. There’s a whole lot to love, even if it is never a match that totally resembles a traditional RINGS main event as it’s often thought of.

RINGS so far has been about the action, and any match with Dick Vrij is going to deliver that, but it’s a little more of the other stuff too — which because it doesn’t often come like this between guys like this, especially with Maeda on the other end of it and especially in a package this tight, makes it stand out even more — and as always, the combination of the two is always going to be worthwhile and the sort of wrestling I like the most.

Another for the “wrestling actually as a sport” file, where rather than just a more realistic style, it’s the idea what sometimes things just happen that communicates that the best, and that makes it the most rewarding.